Alpamayo Circuit is a 140km trek in Cordillera Blanca mountains in Ancash region of Peru. I did the hike from Dec. 23th to Dec. 29th in 2014.

Day 6 (12/28):

I woke up at Tayapama camp in the morning and felt great. It was another cloudy day, but at least it wasn't raining. I had been making swift progress during the hike, and with this pace I would finish the whole thing 2 or 3 days ahead of the 10 day schedule.

By noon I climbed up Paso Caracara and started descending into Ruina Pampa valley. I slowed down to marvel the snow capped mountain ranges, hoping to get a better photo shot of the peaks. By 1pm I arrived at Jankarurish camp. I was dismayed to see that the valley was littered with cow dungs, and herds could be spotted all over the place. After searching around, I did find a spot deeper south free of dung that could be used as a campsite. But it was way too early to set up camp. I normally walk till 1-2 hours before dark. Plus when I looked at the sky, the rain clouds were closing in. It would be really boring to sit alone in the tent for 5 hours doing nothing. I took my backpack off and looked at the map again. There appeared to be only one pass remained – Paso los Cedros, and there's a campsite a short distance after the pass.

Jankarurish camp

Jankarurish camp

I did some calculation and concluded that there would be enough time. At 1:45pm I set off west along Ruina Pampa valley. The trail was in mid-mountain and was unusually good, almost mud-free. 1 hour later it started raining. After 6 days in Andes, I was already used to the weather in wet season. Every day it would rain for at least a couple of hours. I took out my rain coat, rain hat, hid my camera into the backpack and kept charging. By 3:30pm I was at the base of the pass where the trail would turn south. I was a bit later than I had expected. Sun set was 6:30pm and by 7pm it would be pitch dark. So I had a little more than 3 hours to hike over the pass. I looked around but couldn't see anywhere to camp. So I had no choice but to start climbing. I was strangely delighted about this lack of option – I only carried one pack of cigarettes and they ran out at the end of the third day. I kept thinking about the carton I left in the Huaraz, and couldn't wait to get out sooner. The trail winded up the steep mountain, and after 2 hours’ breathless work, I reached the top of the pass at 5:30pm. I took a look at my GPS – the altitude read 4700m. GPS altitude were by no means accurate but it seemed right. I took a few pictures with satisfaction, knowing that this hike was done, and that from this point on I would be descending all the way to Hualcayan.

Indeed, after the pass, the trail started winding down, though not as fast as I had expected. After descending about 100m, then abruptly I found myself picking up altitude again! Already the mist was closing in, and visibility dropped significantly. I hurriedly took out my GPS and had a closer look at the map. I was horrified to see two points of altitude 4740m and 4860m ahead on the trail. It was already 6pm. It meant that I had to climb 200m up and then 600m down in less than one hour. I began running, but it was at over 4500m altitude and I was carrying a 10kg backpack. For every dozen meters, I had to stop to catch my breath. I started to sweat. The temperature was dropping, the mist and rain got heavier. The terrain was mostly moraine, so camping was out of question. By 6:35pm, I finally topped Mt. Osoruri. I was a little relieved - now I just need to find the campsite. By then there was barely any light but the trail could still be recognized. I hurried down until I reached the boulder field where I lost the trail. I took out my headlamp but the mist was too thick for me to see anything. I tried to navigate with GPS, but it was hard to use the touchscreen of my Garmin Oregon 450 with the rain dripping on the screen. So I took a guess and climbed down a few boulders. There was still no sign of trail. I took out the GPS again and this time with some efforts, managed to get it working. I had descended too low. The trail and campsite was above me. I could barely see a thing and the boulders were really slippery. I fell a couple of times chest first onto the boulder.

After a fall into a pound, I was soaking wet. Finally after some desperate scrambling, I spotted a pole over the hill. It was a little house for the aqueduct. I tried to open the door, but it was locked. I looked around – there’s nowhere to camp. I hopped over some boulders, in hope of finding a grassland, but still nothing. Rain had grown heavier by then and temperature had dropped significantly. I made do by pitching the tent next to the tiny aqueduct house, then changed to my camping clothes and got into the sleeping bag as soon as I could. I was already shivering uncontrollably and should I stay in open field for any longer, I would likely get hypothermia. The ground was cement so I had to secure the flyer and guy lines with rocks. Still it was far less ideal than using stakes. With the high wind, the rain still managed to drip into the tent, and before long the sleeping bag was wet. By putting on every clothes I had, I was barely able to stay warm enough. Fortunately the rain stopped by midnight and I survived the cold night.

Next day at 5am, I woke up and started packing everything. By 5:45am just after dawn, I set off and hurriedly started descending. With the daylight, I was now able to see that there were two rows of houses not more than 10 meters back the place where I camped. Those were likely huts to be used by hikers. Looking down the moraine field, it was a cliff dropping more than 100 meters to a small lake. If I hadn’t had the GPS the last night, I might have walked straight down the cliff! The descending trail followed the aqueduct winding down. As I turned around the corner, I took a last look at the camp – it was really a beauty, with snowy mountain peaks as background. But after this incident, scenery no longer brought me any joy and all I wanted to do was to go back to civilization. At 10am, I arrived at the village of Hualcayan with a stiff face on which there’s no delight at all.

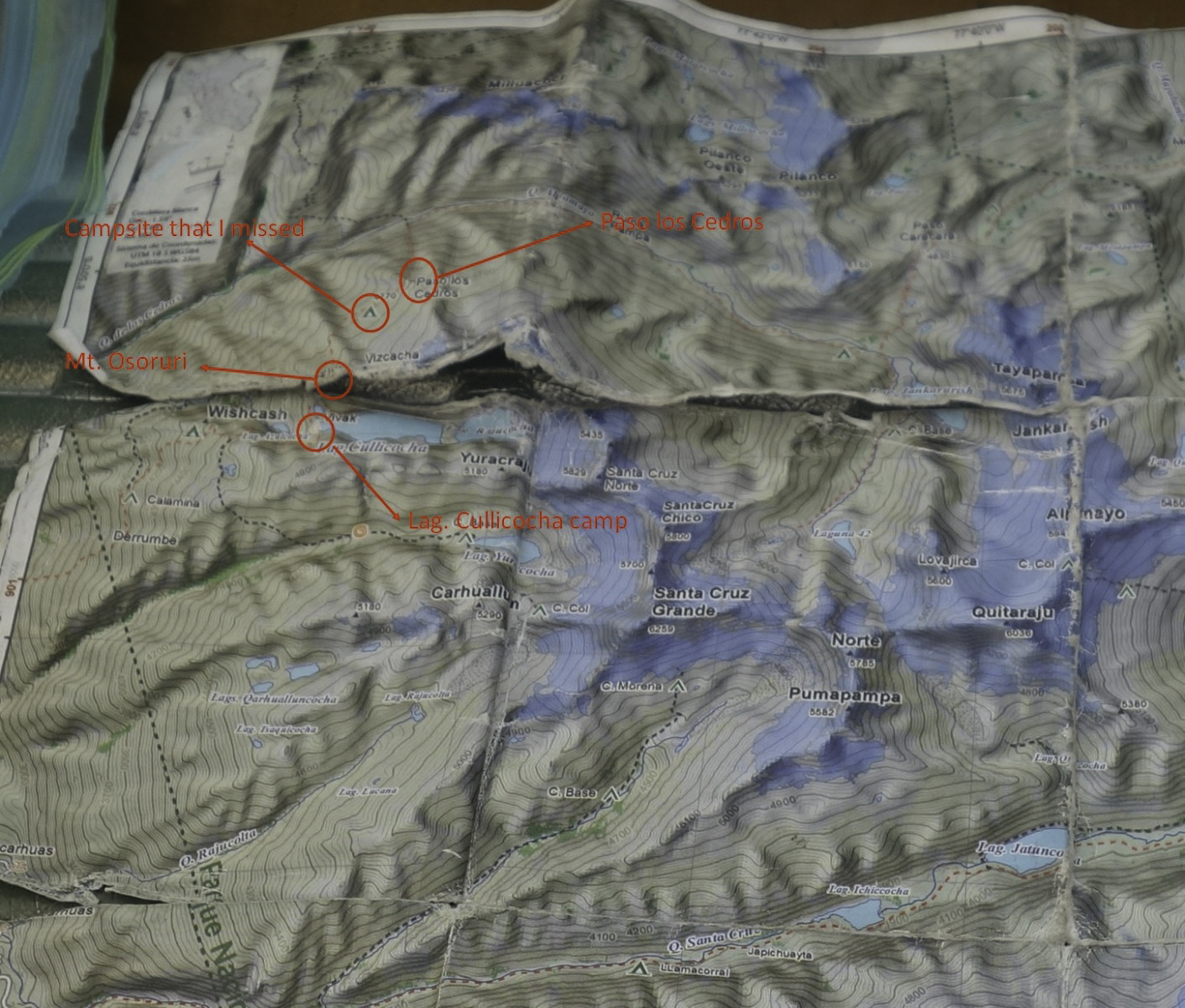

For a long time after the hike, I was very upset as the night before I studied the map, but never saw the latter two passes. I was convinced that inaccuracy of the map was part of the reason I got stranded on the mountain. After I went back from Peru and started looking at the pictures I took, I found a picture of the map that I took the day before the incident. I looked at it closely and was mortified - those passes were actually on the map. They were right on the folds! Because of the rain and bad paper quality, the map broke into pieces just a couple of days into the hike, making the details near the folds hard to recognize. Without a close inspection, I conveniently assumed that Paso los Cedros was the last pass on the trek.

I then compared with other maps online. Sure enough - I walked all the way to Lag. Cullicocha! Now everything made sense. Just after Paso los Cedros when I was descending, I did see some flat ground and a tiny pond. I even made a comment that this would make an okay campsite. This IS the campsite I was looking for.

In my recent years, I had thought that I learned from mistakes in my earlier hikes and I was in control of the situation. Then this incident happened and I realized that I was still a novice hiker. I am grateful that in the end I survived to tell the story. The few things I learned:

- Get a good map. Read it carefully before the hike and memorize the approximate positions of passes, campsites, water sources. Had I noticed Mt. Osoruri pass before the water damage, I probably wouldn't have missed the campsite.

- Leave enough time for pass crossing. I normally hike till it’s almost dark. This way I could cover more mileage every day and finish faster. But outcome of being caught near the pass was disastrous as there would be nowhere to camp. I should always leave enough buffer time for that.

- Sometimes the best option is to turn back. In retrospect, the only chance to get back to safety after I realized the trail started climbing up is to backtrack to that flat ground I saw earlier. Somehow at that moment I rejected this options, probably because to do so I needed to pick all the altitude back. But certainly it was much better than getting stranded on the mountain with nowhere to camp.

- Trying to quit smoking during a hike is unwise. One of the reasons why I decided to push on was that I craved for the cigarette I stored in Huaraz. If only I had a pack with me, I probably would stayed at Jankarurish camp. Smoking is bad for health and I am still trying to quit, but not during a hike (I do pack out all the cigarette butts). Lack of nicotine really clouded my thinking and will put me to danger.

Other than this incident, the trek went rather smoothly.

Logistics

I arrived at Lima at 9pm on Dec. 21st 2014. After collecting my luggage, I immediately took a taxi to Plaza Norte and hopped on an overnight bus to Huaraz. It was a comfortable 8 hour bus ride. I soon fell sound asleep on the 160 degree semi-cama. Huaraz is moderate town at the altitude of 3100m. In December, there were few tourists in town (a sharp contrast to Cusco). There are a few supermarkets and tiny gear shops selling maps and gas canisters at town center.

Huaraz

Huaraz

The next morning, I took the combi to Caraz near the river Rio Quilcay north of town. Combis run every few minutes, and cost $6. At Caraz, it’s a 10 minute walk across town to the collectivo plaza, where you can hop on a collectivo (shared taxi) to Cashapampa.

Cashapampa

Cashapampa

On the return at Hualcayan, you need to take a taxi ride to Caraz (alternatively Cashapampa is about 1 hour’s walk away). There’s only one taxi in the village, so you might have to wait for a while if the driver is out. The ride is about 1.5 hours mostly on dirt road.

Hualcayan

Hualcayan

Weather

Summer (November to March) is the wet season. During my week-long trek, it rained at least a couple of hours every day. It even hailed twice. When it was not raining, it was more often cloudy than sunny. Views of mountain peaks were often blocked by the clouds. In my opinion, the trek is probably more enjoyable during the dry season. It would be colder but the views are definitely more impressive. I did the trek in December only because my summer was backlogged with so many hikes and Peru is not on top of that list. In winter however, there are not many places I wish to go. So after I read the Backpackinglight article, I decided to give Cordillera Blanca a try. On the bright side, December did offer enough solicitude, if that’s important to you. I met a couple the first day doing the circuit, two guys and a tour group the second day doing Santa Cruz trek, and that’s all the hikers I met in seven days. Besides occasional encounters with locals, you have the trail to yourself (with the herds).

Herds

In Peru, like in most other third world countries, trails are there for a reason. Most of the 140km of Alpamayo Circuit have been herders' footpaths for generations. Encounter with herds of cows, donkeys, horses, sheep and llamas are inevitable. Sometimes you need to "negotiate" with them the right of way. The only way of "negotiation" I know of is throwing rocks and shouting curses. Of the few dozens of confrontations, this worked every time. But you may want to look for an escape route first, just in case.

Most of the trail, save for the high passes, was littered with herd dungs. Situation was worst in Tupatupa valley. There was simply no dung-free spot to camp in the entire valley. If there's fresh dung near the camp, there's a high probability that the next morning animals would be back. I learned it the hard way the first two days. While I was chilling near camp at 9am, enjoying the rare sunshine, a group of ox showed up and stared at me angrily. This situation is especially bad as they could simply destroy my tent, and my hike would be over. Fortunately a few rocks was enough to drive them off. After that, I set up alarm clock for 6am every time and break camp before 8:30.

Trail Conidition

Generally speaking, the trail was easy to navigate. There were a few tricky parts around the establishments. I never found the trail to Paso Tupatupa. There were a lot of herding in the valley, and a lot of side trails and animal trails as a result. I thought I was on the right one, but before long it drifted west towards Mt. Taulliraju. In the end, I was forced to go off-trail, and climbed over a random hill.